5月5日,是馬來西亞選舉史上投票率最高的一次,整個馬來西亞有80%的選民走向投票站。選舉委員會首次為了海外馬來西亞公民設置通訊投票,在這之前通訊投票只有政府職員或政府資助的學者能行使。對於海外選民來說,要投下他們手中的一票非常不易,他們必須在2012年底前完成註冊,亦即,在明確的投票日期前五個月,跋涉至特定的外交單位完成註冊(有些甚至超過1000公里遠)。

2013年第十三屆大選是一場執政聯盟與在野聯盟的長期戰鬥,反對黨(由PKR-公正黨、DAP-社會主義結盟黨和PAS-伊斯蘭黨組成)試圖從這世界上,經由選舉存活最久、已經統治55年的國民陣線(BN)奪取政權。在第十二屆大選時,由極具魅力的Anwar Ibrahim所領導的反對黨突破政治封鎖,贏得超過三分之一的國會席次。這個強而有力的結果,加深了許多選民對第十三屆大選的期望,同時也讓國民陣線充滿挫敗感。

在選舉準備期間,有無數關於選舉詐騙及騷擾的新聞,包括已註冊的選民消失於選舉名冊中,威脅要註銷社會主義結盟黨反對黨的資格;此外,還有令人費解的南菲律賓私人軍隊入侵,聲稱有反對黨人士涉入的假造性愛影片等等多種伎倆。甚至有人聲稱馬來西亞政府以飛機載送了大量的非法選民進來,包括孟加拉、緬甸、巴基斯坦及其他鄰國的公民,而且他們被非法地給予身分證及投票權,並被公車載往投票站。政府似乎將它所有的一切都投入了選舉,包括合法及非法的,企圖要維持它的權力。

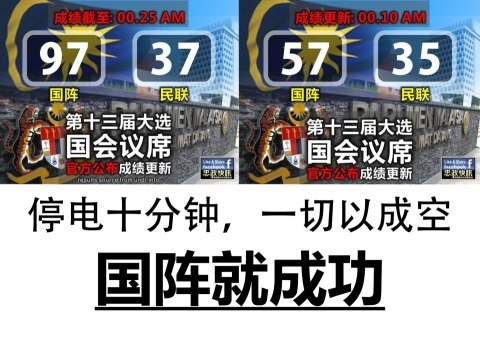

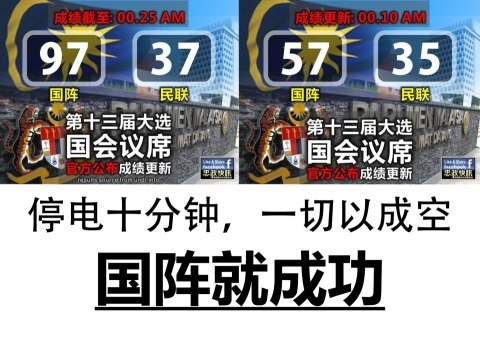

當晚結束前,投票結果就已經非常顯而易見。雖然執政黨國民陣線失去了選票,相較於反對黨人民聯盟(Pakatan Rakyat, PR)的51%,國民陣線只贏得了46%的選票;不過,國民陣線仍贏得了國會中大部分的席次,以133席領先反對黨的89席。這個得票率與席次的差異與不一致,就是選區劃分不公所造成的。

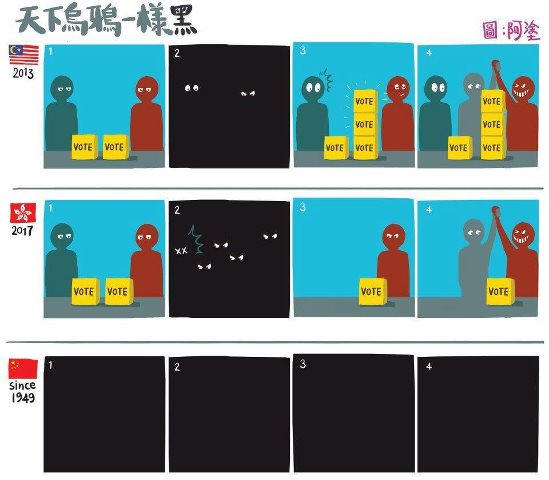

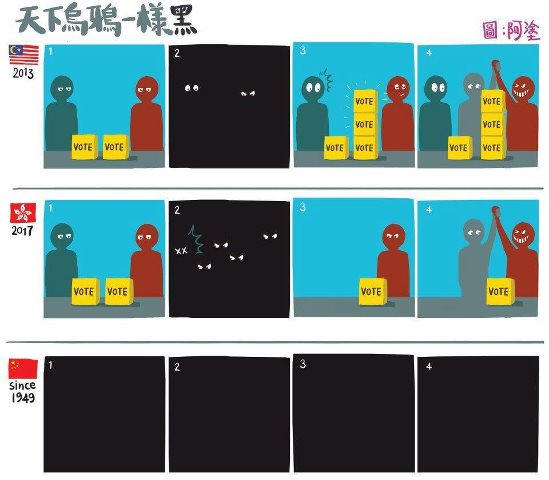

馬來西亞國會席次問題的差異高達二十倍。例如,有些席次選區只有約5,000個選民,而有些席次選區卻超過100,000個選民。還有許多騙局與騷動情況影響了當晚的選舉,包括選民抱怨許多地區在計票時發生了刻意的停電事件,使得國民陣線獲得額外的選票箱,改變了許多聯邦及州席次的結果。前述情況發生在許多人民聯盟已明顯領先的州。為了阻止這種舞弊發生,在Lembah Pantai,也就是Anwar Ibrahim女兒Nurul Izzah選區所在地,當地居民在投票站關閉許久後,上街封鎖街道,試圖阻止據傳載送著作弊選票的警車通過。

令人感到驚訝的是,儘管再獲政權的總理Najib Razak對於「華人海嘯」(Chinese Tsunami)提出了抱怨,其他執政黨人也紛紛猜測華人選民對於政府並不領情、也不再忠於政府。儘管馬來西亞是一個相當和平的多種族國家,由於1969年5月選舉之後爆發的反華、反印度種族暴動,使得選民心頭仍縈繞著極端的恐懼感。

Najib的言論暗示了這樣的事實:由多種族(馬來、印度、華人)、但大部分為華人組成的社會主義結盟黨贏得了國會的勝利,然而同盟的公正黨、伊斯蘭黨席次卻下降。總理的言論極具挑撥地顯示了國家種族政治的問題,以及一些領導者利用種族意識傾向與恐懼來對付競爭對手,而這些作為,都與國民陣線官方自身為了種族和諧制定的「一個馬來西亞」(1 Malaysia)政策完全衝突。

華人選民(主要為城市居民)的確是背離了國民陣線,但許多都市的馬來族選民以及其他種族的馬來西亞人,也都在都市及鄉村選民之間顯現出了明確的劃分,而並非如國民戰線亟欲宣稱的那樣,在華人選民及馬來族人之間有明確的區別。

國民陣線在都市區域投注越來越少的資源與在野黨競爭,國陣只投資在一些關鍵區域,特別是一些被鎖定為伊斯蘭黨和公正黨席次的區域,例如由Nurul Izzah所領導的Lembah Pantai。很明顯地,國陣將公正黨及伊斯蘭黨視為對國陣據點、馬來族選民及政權延續的最主要威脅。同樣值得思索的是,投給國民陣線的馬來族比例是否如同觀察到的那麼高,或者只是大量持著偽造身分證的外國非法選民、以及幽靈選民,導致了數字的膨脹。

選舉的結果使得期望更換政府、或至少反對黨能獲得更多勝利的馬來西亞選民(至少佔了50%的人口)感到憂慮。的確,大部分的獨立投票站都預測反對黨即將獲勝。先前第十二屆大選的結果,振奮了許多馬來西亞人,並促使選民更關心政治。這個選舉結果,自然而然地,可以預期許多馬來西亞人對政黨輪替幻想破滅,並再次對下一個五年任期間的政治發展,以及選舉委員會對於選舉舞弊裝嚨作啞進行「檢驗」。一些評論家已經指出,在選區劃分不公仍到處充斥的情況下,人民聯盟不可能獲得勝利。但,許多馬來西亞人似乎比過往還更加有決心要努力迎向改變。

對馬來西亞而言,有一個危機隱身在其鄰國背後。在不久前,馬來西亞相對印尼仍猶如民主的指路明燈。十年過後,印尼正在發展的民主卻已經遠遠超越了馬來西亞既有的體制。至於緬甸,或許不必太久也能如此。由於前所未有的選舉舞弊嚴重,以及人們察覺到政府缺乏統治正當性而引起的大規模街頭集結、抗爭等等,這些都會再次將各種種族的馬來西亞人團結起來,朝向共同的理想邁進。

The Results of Malaysia’s 13th General Election: An Outcome Tarnished by Fraud

It was the biggest turnout in Malaysian electoral history – 80 per cent of voters made their way to election booths all over Malaysia on 5th May. For the first time the Electoral Commission organised “postal voting” for Malaysian citizens overseas, previously only allowed for Government employees or government-sponsored scholars. It was not easy for overseas voters to cast their ballot – they had to register by the end of 2012, five months before the election date was even known, and many had to travel to specific diplomatic posts (in some cases more than 1000 kms). Many overseas Malaysians who missed the postal vote deadline decided to travel back to Malaysia to cast their votes, and within Malaysia many took the trouble to travel to their home towns to vote where they were registered.

The 13th General Election was round two of an ongoing battle by the Opposition (a coalition of PKR – the justice party, DAP – Democratic Action Party, and PAS – the Islamic party, known collectively as Pakatan Rakyat, or PR) to wrest control from the Barisan Nasional Government (BN), one of the longest serving governments in the world, having lasted more than 55 years of continuous rule. During the 12th General Election the Opposition lead by the charismatic Anwar Ibrahim made a political breakthrough, winning more than one third of parliamentary seats. This strong result had raised expectations for the 13th General Election for many voters, as did a growing sense of frustration with BN. In the lead up to the election there were countless media items about electoral fraud and harassment including registered voters disappearing from the electoral roll, threats to deregister the DAP opposition, a mysterious invasion by a private army from the southern Philippines, fake sex videos purporting to feature Opposition figures and numerous other tactics. There were even allegations that the Malaysian Government flew in planes full of illegal voters, citizens of Bangladesh, Burma, Pakistan and other neighbours, who were given identity cards and voting rights illegally and bussed to election booths. It was as if the Government was throwing everything it had at this election, legitimate and illegitimate, in a desperate bid to stay in power.

The result was very clear before the end of the night. Although BN had lost the popular vote, winning 46 per cent of the vote compared to 51 per cent won by PR, the BN Government clearly won a majority in Parliament, 133 seats to 89. This great discrepancy is due to rampant gerrymandering. The factor of difference between some seats in the Malaysian Parliament is twenty fold – for instance, in the previous election there were some seats of only around 5,000 voters, while others may be over 100,000. Ever more disturbing stories of fraud coloured the election night, including complaints in many areas that electricity blackouts were orchestrated during counting to allow BN to bring in boxes of votes and alter the outcome of several Federal and State seats. This happened in several states where PR had been clearly leading. In Lembah Pantai, the seat of Anwar Ibrahim’s daughter Nurul Izzah, residents took to the street to blockade police cars allegedly delivering fraudulent ballots to the counting booth, long after the polls had closed.

Alarmingly, despite winning back Government, the returned Prime Minister Najib Razak complained about a “Chinese Tsunami”, and others also suggested that Chinese voters had been ungrateful or disloyal to the Government. Although Malaysia is a fairly peaceful multi-racial country, an underlying sense of fear haunts the electorate due to deadly anti-Chinese and anti-Indian racial riots which broke out following the May 1969 elections. Prime Minister Najib’s comments allude to the fact that DAP, a multi-racial but largely Chinese party, made the biggest gains in the Parliament, while PKR and PAS support dropped in favour of BN. The Prime Minister’s comments are a provocative and troubling reminder of the country’s racial politics, and the tendency of some leaders to play races off against each other using fear, in stark conflict with the BN Government’s own official “1 Malaysia” policy for racial harmony.

It is true that Chinese (who are predominantly urban-based) voters deserted BN, but it is also true of many urban Malay voters and Malaysians of all races, indicating a divide between the urban and the rural voter, not the Chinese and the Malay voter as the BN is so desperate to claim. BN put fewer resources into contesting urban areas except for a few key ones, and specifically targeted a number of PAS and PKR seats, such as Lembah Pantai, the seat held by Nurul Izzah. It is clear that BN identified PKR and PAS as the most serious threat to BN’s natural constituency, Malay voters, and therefore continued rule. It is also worth wondering if the Malay vote for BN was as high as perceived, or whether there were significant numbers of foreign illegal voters holding identity cards fraudulently inflating those numbers as well as phantom voters.

The outcome is deeply distressing for those Malaysian voters (50 per cent of the population at least) who were anticipating a change in Government, or at least more significant gains by the Opposition. Indeed most independent polling suggested an imminent opposition win. The results of the previous election, the 12th General Elections, had excited many Malaysians and helped voters to become more engaged in the political process. It would be natural to expect many Malaysians to become disillusioned and once again “check out” of the political process with the next election five years away and the Electoral Commission deaf to allegations of electoral irregularities. A number of commentators have suggested that the PR Opposition will not win while gerrymandering is so rife. But many Malaysians seem more determined than ever to work towards change.

There is a danger for Malaysia that it will slip behind its neighbours. Not long ago, Malaysia seemed like a beacon of democracy when compared to Indonesia. Ten years later and Indonesia’s fledgling democracy has far surpassed Malaysia’s established system. It might not take long for Burma to do the same. There is every chance that due to the unprecedented levels of electoral irregularities, the perceptions of the Government’s lack of legitimacy may end up in more massive street rallies and protests, once again bringing together Malaysian of all races and all backgrounds towards one cause.