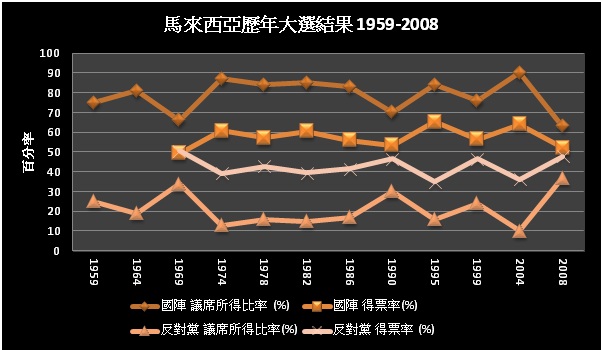

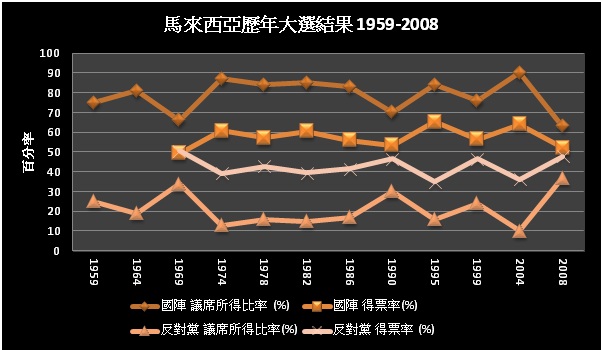

(編者註:2013年5月5日,馬來西亞將舉行第十三屆國會大選)當馬來西亞總理Najib Razak在今(2013)年4月3號宣布國會解散時,為長期以來,人們對於大選的種種猜測畫上了句號。在2008年3月8號的第十二屆大選中,反對黨在國會中獲得了前所未有的勝利,並且根據選票計算,反對黨甚至在西馬取得了得票率上的勝利。儘管反對黨在222個席次當中從原先的19席增為88席,然而由於選區的劃分不公,前述的現象並未反映於國會當中。

一夕之間,馬來西亞的政治從單一政黨轉為兩黨體系。而這對於大部分的馬來西亞選民而言宛若留下了一種「未完成事業」之感,也因此對於接下來的選舉有很高的期盼與興趣。儘管馬來西亞的選舉週期為五年,在最後兩年的時候人們就已有選舉將至的感覺,而人們的期待感則隨著一次又一次的危機及預測而被拖延。選舉的日期現已確定為5月5號。

第十二屆大選的結果在當時被廣泛地形容為是一場「海嘯」,而的確如海嘯一般,它重塑了馬來西亞的政治面貌。自從獨立以來,馬來西亞已連續55年受國民陣線(Barisan Nasional, BN)統治,其為三大政黨的聯盟,由馬來民族統一機構(United Malays National Organization, UMNO)所領導。

在1969年5月的大選中,當時執政的聯盟政府喪失了大部分的選票,而爆發了強烈的反華及反印度的種族動亂,使得馬來西亞選民的集體心理感到畏懼。一直到第十二屆大選時,馬來西亞人仍躲避著政治-投票並非強制性的,因而馬來人在心理上及實際行為上都不願參與政治過程。許多人不參與政治,是因為對選舉違法亂紀無能為力而感到絕望,同時也害怕另一次種族大屠殺發生。

反對黨在第十二屆大選中的重大勝利,完全重塑了馬來西亞人對於選舉體系的心理。人們對於所有政治事務、選舉透明化的監督及期望都有了全新的興趣,而這在十年前,是難以想像的。這對於選民及政治人物來說,都顯露了馬來西亞民主化的可能性。同時這也給予了選民些微力量,而這些力量是他們作為選民本就一直該擁有的,只是他們從未真正相信或給予其信心過。

在今天,馬來西亞的選民已了解這股力量,並且大部分選民都迫不及待地想要對改變發揮影響。當前,馬來西亞選民面臨了一些造成他們憂慮、並且影響投票意向的議題。這些議題,包括了不斷加劇的犯罪率所造成的動盪不安,對於數十萬非法移民發放身分證的問題,以及南菲律賓300名小型武裝者對於國境東邊沙巴的入侵問題。另外,還包括了更重要的問題,如根深蒂固的種族分化、貪汙、法律規範的不一致、選舉的欺騙行為等等,這些也是選民所關注的議題。

國民陣線害怕選舉變化的可能性,然而現實是,選舉的失敗將會給予國民陣線及其組成政黨一個絕佳的機會,以及最大的誘因進行重組、並在未來維持影響力。國民陣線的三個主要組成政黨都是以種族作為成員資格限制,馬來民族統一機構限定馬來人才能加入,泛馬來西亞印度人國民大會(Malaysian Indian Congress, MIC)限定印度人才能加入,而馬來西亞華人公會(Malaysian Chinese Association, MCA)則限定只有華人才能加入。國民陣線的主要政綱是一個稱為「馬來人至上」(Ketuanan Melayu’ or Melayu/Malay racial supremacy)的社會合約。這個合約的前提是認為積極的歧視,以及對於特別種族特權的保護可以帶來平等及安定。

對於國民陣線來說,問題出在它的政綱與現代潮流不一致,而它對於自身種族優位性的政綱,越趨挑釁的詮釋方式也使得越來越多人民遠離他們。持續增長的宗教不容忍(religious intolerance)和種族沙文主義,伴隨著看似猖獗的高層級貪汙,都削弱了政府的聲望。

此外也有人主張存在大量的選舉詐騙,尤其是國民陣線為了提升支持度而引進數百萬非法移民的移民計策。單單在沙巴這一州,據估計就有約800,000的南菲律賓人,而在整個馬來西亞也估計有3-4百萬的印尼非法移民。因此,甚至馬來西亞人自身也開始感到疏遠感,有許多馬來人對於印尼人、菲律賓穆斯林、孟加拉人、巴基斯坦人及緬甸穆斯林感到憤恨不平,因為他們不但被允許非法移民至馬來西亞,他們還甚至被允許擁有公民身分、並能夠正式地變換種族身分而成為馬來人。在「馬來人至上」政綱50年後,所有種族的馬來人開始理解到在現實生活中,特權只給予一小部分的馬來菁英及與其友好者,而不平等及歧視則給了其他所有人,包括華人、馬來人、印度人、土著、歐亞混血者等等。

相較之下反對黨則由三個意識型態政黨所組成,公正黨(Parti Keadilan Rakyat , PKR)、伊斯蘭黨(Parti Agama Semenanjung, PAS)、和社會主義結盟黨 (Democratic Action Party, DAP)。國民陣線主張的種族政治和種族隔離,與反對黨主張的種族多元、宗教多元與合作等政策相較,國民陣線顯得過時。

上述三個政黨在官方上都是多元種族的,且非穆斯林者也可以加入伊斯蘭黨並被預選為候選人。最近社會主義結盟黨的「火箭」競選標誌使得他們無法出現於選票上,而他們的夥伴正義黨和伊斯蘭黨出手援救,讓社會主義結盟黨的候選人改以這兩黨的競選標誌進行參選。此外,與現任政府將會有災難性失敗的預測,反對黨在上一次選舉中贏得政權的幾個州政府仍未垮台或殆盡,反而極為成功並且展示了透過透明化,以及負責的作為。

第十二屆大選的結果,會是馬來西亞改革成為現代國家的正向步伐,帶來了更高的透明化、責任政治、政治諾言,也使選民更加認知到自己的確是個政治上的公民。在先前政府與人民之間的那套溫和專制主義,特別是透過Tun Dr Mahathir二十年來的政權而具體化呈現,現在已經來到了盡頭。第十三屆大選為馬來西亞人帶來一個契機,能夠與一個負責任、有代表性的、由人民直選出來並對人民負責任的政府,一同去深化他們的民主改革。

原文

Malaysia's 13th General Election: A Turning Point for Malaysia

When Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak announced the dissolution of Parliament on the 3rd April 2013, it brought to an end a long period of speculation about the upcoming General Election. The 12th General Election on the 8th March 2008 saw the Opposition make unprecedented gains in the Parliament, and according to most calculations, even won the popular vote in Peninsular Malaysia. Due to gerrymandering, this was not reflected as well in the Parliament, although the Opposition did increase its seats from 19 to 88, out of a possible 222. Overnight, Malaysian politics was transformed from single party rule to a two party system. This has left a feeling of ‘unfinished business’ for many Malaysian voters and there has been keen anticipation and interest in the upcoming election. Although Malaysia has a five year electoral cycle, for the last two years there has been a sense that the election was imminent, and that expectation has dragged on through crisis after crisis, and prediction after prediction. The election date has now been set for the 5th May.

The results of the 12th General Election were popularly described as a “tsunami” at the time, and like a tsunami, it has reshaped the political landscape. Since independence, Malaysia has experienced more than 55 years of continuous rule by Barisan Nasional (BN), a coalition of three major political parties lead by UMNO (United Malays National Organisation). Following the May 1969 elections, the one occasion when the ruling coalition did lose some power at the ballot box, deadly anti-Chinese and anti-Indian racial riots broke out which scared the collective psyche of the Malaysian electorate. Until the 12th General Election, most Malaysians steered clear of politics – voting is not compulsory and many Malaysians mentally and physically opted out of the political process. Many did not participate because there was a perception of hopelessness, insurmountable electoral irregularities and fears of another racial slaughter.

The significant gains that the Opposition made at the 12th General Election have completely reshaped the Malaysian psyche regarding the electoral system. There has been a fresh and renewed interest in all things political and a scrutiny and expectation of transparency that would have seemed unthinkable a decade ago. It was a revelation for both electors and politicians alike as to the possibilities for democracy in Malaysia. It gave the electorate a glimpse of the power they as voters had always had, but never really believed in or had confidence in.

Today the Malaysian electorate understands its power and many voters are impatient to affect change. The Malaysian electorate is currently facing many issues that cause disquiet and will be on voters’ minds when they cast their ballots. There is unrest about spiralling crime rates, the distribution of identity cards (citizenship) to hundreds of thousands of illegal immigrants, and the invasion of a small armed force of 300 fighters from the southern Philippines into the eastern state of Sabah. But larger underlying problems such as the deep seated racial divide, corruption, inconsistencies in the rule of law and perceptions of electoral fraud are also of concern.

Barisan Nasional looks at the possibility of electoral change with fear, however the reality is that electoral failure will give BN and its component parties the best chance and the biggest incentive to reform and remain relevant in the future. BN’s three major component parties all have race based memberships - UMNO (United Malays National Organisation) for Malays only, MIC (Malaysian Indian Congress) for Indians only, and MCA (Malaysian Chinese Association) for Chinese only. The primary platform of the BN is a social contract called ‘Ketuanan Melayu’ or Melayu/Malay racial supremacy. The premise was that positive discrimination and protection of special racial privileges leads to equity and stability.

The problem for the BN is that its platform is inconsistent with modern values, and the increasingly aggressive interpretation of its racial supremacy platform has alienated many people. Growing religious intolerance and racial chauvinism, coupled with seemingly rampant high level corruption have undermined the popularity of the Government. There have also been allegations of massive electoral fraud and in particular the use of immigration fraud to boost the support for BN through bringing in millions of illegal immigrants. In the state of Sabah alone, it is estimated that there are up to 800,000 southern Filipinos. There are also an estimated 3 to 4 million Indonesian illegal migrants in Malaysia. Thus, even the Melayu (Malays) themselves have begun to feel alienated and many are very resentful that Indonesians, Filipino Muslims, Bangladeshis, and Pakistanis and Burmese Muslims have not only been allowed to migrate illegally, they were also given citizenship and were also allowed to change their race to officially become Melayu/Malay. After 50 years of Ketuanan Melayu, Malaysians of all races have come to realise in reality it means special privileges for a small Malay elite and their cronies, and inequity and discrimination for everyone else, Chinese, Malay, Indian, Indigenous, Eurasians and others.

The Opposition in comparison are comprised of three ideological parties, Parti Keadilan Rakyat (PKR – the justice party), Parti Agama Semenanjung (PAS – an Islamic party), and DAP (Democratic Action Party – a socialist aligned party). BN’s racial politics and segregation seem out dated when contrasted with the multi-racial and multi-religious collaboration of the Opposition parties. All three are officially multiracial, and non-Muslims can join PAS and be preselected as candidates. DAP recently had its ‘rocket’ logo deemed unacceptable for printing on ballot papers – its partners PKR and PAS have come to its rescue, allowing DAP candidates to run under the PAS and PKR logos instead. Additionally, contrary to predications of calamity by the incumbent Government, Opposition held State Governments won during the last election have not crashed and burned, but rather have been extremely successful and have demonstrated what can be achieved through transparency and accountability.

The changes brought by the 12th General Election have been a positive step in Malaysia’s evolution as a modern state, bringing greater transparency, accountability, political engagement and greater awareness for voters of their own role as citizens. The paternalistic relationship the Government has previously had with its citizens, as personified by Tun Dr Mahathir’s twenty year reign, is at an end. The 13th General Election hails a unique opportunity for Malaysians to further their democratic evolution with an accountable and representative Government directly elected by the people and directly accountable to its people.